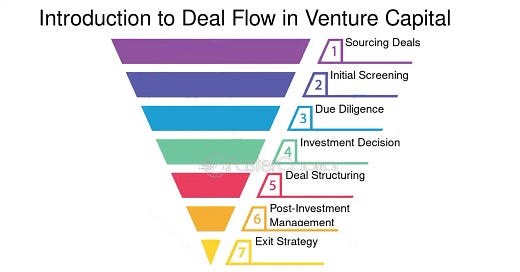

The basic idea behind VC investing is that early stage companies have the potential to generate material future free cash flows even though all start off as loss making entities. The individual or collective brilliance of the founding team will either tackle an existing market, create a new one, or solve a pain point that has to that point been solved ineffectively. Many startups will fail. This is because generally status quo attempts to choke the life out of a startup every single day. Failure may come from no market fit, failed execution, entrenched competition, insufficient capitalization, a bad business model, bad hiring, bad founders, or bad luck. Typically some combination of these external and internal factors collectively result in the demise of early stage companies, but from my perspective most startups fail because the founders seek to solve a problem the market deems irrelevant. Faster Capital produced the image below which is a helpful overview of the process.

Corporate VCs approach the business with a double bottom line focused on strategic return and financial return. The strategic return comes from smart CTOs at the startup and the investment company collaborating, the startup building on the investment companies infrastructure, joint customer wins that spawn from the partnership, and of course any marketing the corporate investor can do to tout that they are investing on the leading edge of their chosen market. The financial return feeds into portfolio management and venture math which will be addressed in parts two and three of this series but the basic idea is to, e.g., generate a 5x - 10x return. Cash-on-cash or multiple of investment capital are common ways to discuss venture returns. For example, invest $1M and receive $5M after an investment hold period of three to seven years.

Corporate VCs typically invest directly off of their balance sheet and do not raise a separate dedicated fund. Typically $25M to $100M in cash may be earmarked and or announced to invest for a specific purpose. The corporate investors typically are not general partners per se and are simply at-will regular employees with no opportunity to earn carried interest. So even if one investment generates material returns for the corporate VC he or she is unlikely to receive any direct economics from that and at best such VC can argue for increased bonus or RSUs in the next corporate compensation cycle. Still, a conscientious corporate VC will want to do well to continue to make future investments. The largest corporate VCs include, e.g., Google Ventures (GV), Intel, Salesforce, Cisco, Microsoft, AWS and Qualcomm. I worked at Dell Ventures where we announced a $50M dedicated fund and deployed capital into storage companies. As a result I came to visit or know some of the other large corporate VCs at some of the hyper scalers mentioned above in addition to institutional VCs who often led the round.

Institutional VCs typically raise a dedicated fund from limited partners including insurance companies, pension funds, high net worth individuals, and the general partners of the fund itself. The general partners typically put material capital at risk right alongside their institutional investors so both are aligned to drive financial returns. General partners may take a 2% carried interest on the fund for operating purposes. For example, a $100M fund might generate $2M in annual management fee to fund GP wages, office space, and deal expenses for lawyers and accountants. However, the real capital to be made is on the carried interest on that $100M fund. For example, if the net realized proceeds of the $100M fund turn out to be $500M, then after returning $100M to limited partners, the GPs may earn a 20% carried interest in the $400M gross gain on investment or $80M. So over the course of, say, seven years this hypothetical VC might generate $82M in fees to split mainly among its senior most team members. Of course, not every venture capitalist is going to generate returns in excess of their chosen benchmark, e.g., the NASDAQ or S&P 500, and typically those funds that end up in the bottom quartile may not be able to raise their next generation fund as a result. Meanwhile funds with top quartile returns may be able to market their success to existing and new institutional investors to raise another larger fund to repeat the entire process.

Pricing venture capital deals is an art and typically institutional VCs are better armed to do that than corporate VCs. Internal databases of pre-money valuations are critical as these aren’t always available in Pitchbook, CapitalIQ, Crunchbase, or CB Insights. It may take personally knowing CEOs, being in direct dialogue with them, and building a database of valuations at various stages over time. Of course, there are also law firms who may post aggregate quarterly information on the venture deals their firms work on. Historically, Cooley, Wilson Sonsini, Fenwick & West, Goodwin Procter and other law firms have posted anonymized quarterly summaries of venture deal terms based off of the specific transactions they have worked on. As an aside, the PWC MoneyTree report is now produce in collaboration with CB Insights and historically that report has been high quality even though it is higher level.

Deal flow is the life blood of VC and the best deal flow is typically going to go to the largest, most pedigreed, and successful institutional VCs. This means corporate VCs need to cultivate relationships with those firms plus CEOs and founders in the chosen investment niche. Because fundraising is painful and time consuming for CEOs, institutional investors who know the market and can act decisively are valued. Because taking capital from a corporate VC can single a tighter partnership with them, that may chill the prospects of that startup partnering with competitors of that corporate investor. In the worst case scenario, a startup CEO will have an actual right of first negotiation (ROFNs) forcing them to divulge the details of any inbound acquisition offer. ROFNs are bad for both the startup and the corporate VC since both parties should want as many unfettered strategic exit options as possible.

In VC most business diligence is done before a term sheet is delivered to the CEO. That diligence can include technical reviews, executive team presentations, financial diligence, and detailed discussions on use of proceeds. A term sheet will outline how much capital the lead VC is willing to deploy, at what valuation, in what time frame, and other ancillary terms that outline what is to come later in a definitive document. Term sheets are typically two to four pages and are a business hand shake before real legal fees are spent on drafting, e.g., a new series A preferred stock agreement, investor rights agreement, restated certificate of incorporation, disclosure schedules, and so forth which can all be quite voluminous in the aggregate. A term sheet helps VC and CEO agree on the basics before wasting time. Typically valuation is the most important term to the CEO and his or her board because that directly impacts the economic future of all involved.

Startup valuations can vary wildly based on the team, total addressable market (TAM), financial or operating plan, and potential exit options available to the startup. Precedent VC deals of similar companies at that stage, in that geography, and with similar characteristics may not always be available. Smart CEOs will not want to raise at the highest possible valuation in a hot market because that may set them up for a down round at a lower valuation in the future. Down rounds reduce and may eliminate equity upside for key executives at the startup who may chose to leave and reducing the potential for a successful exit outcome.

The earlier stage the company, the more important that the right team is in place. A founder who has had multiple successful $100M exits may command a higher valuation than a first-time founder who may struggle to raise any capital at all. Founders are absolutely critical to startups because their individual brilliance, sweat equity, sheer determination, ability to attract and hire, ability to execute and many other factors will make or break a startup. Internally they must be excellent because again externally there are many factors that conspire to choke the life out of a startup.

TAM is also important because it speaks directly to how large a startup can become. Not all startups will become unicorns with valuations exceeding $1B. Many limp along in the $100k to $5M revenue range which actually might be a good outcome for a sole founder, bootstrapped CEO who can live a comfortable lifestyle off of that. For any VC looking to generate a return however, they are typically looking for companies that have the potential to get to $100M in revenue because that means more exit options to strategic buyers, private equity firms, or even the initial public offering (IPO) markets. A TAM that is too small places a ceiling on the revenue upside of a startup and simply may not be investable. I often tell founders their TAM should be between $2B and $20B. Below $2B is likely too small for a startup to obtain a meaningful foothold for growth over time. Above $20B I tell founders to think of Serviceable Addressable Market (SAM) and Serviceable Obtainable Market (SOM) to niche down to something practical. This is because no startup ever has signed their first deal approaching even $1B.

By now you should be knowledgeable enough about the VC market to know where you need to learn more. Or if your mission was to simply drop knowledge bombs at your next cocktail party you know have all the ammunition you need for that. If you’re a practitioner you should investigate the National Venture Capital Association (NVCA).

Disclaimer: All thoughts herein are my own and no warranty is either expressed or implied. All names, trademarks, service marks, images, or likenesses are the property of their respective owners. Nothing herein should be construed as either financial or legal advice. You should seek a competent advisor before entering into any transaction. There is no obligation on the author to update this or any materials in the future should facts or circumstance change.